How garden tourism is making a difference in Australia

During my consulting years I had opportunities to reach out to the global community and showcase the management and development of public programs, exhibitions and publications in Australian museums and botanic gardens.

I was invited to present at the Garden Tourism Conference in Toronto, Ontario, 16-18 March 2015. This came about because of collaborations with Dr Richard Benfield, Professor of Geography, Central Connecticut State University, USA and Chair, International Garden Tourism Network. Richard is best known for his book ‘Garden Tourism’ published in 2013. His latest offering ‘New Directions in Garden Tourism’ (2020) provides an update on the statistics and growth of the global phenomenon of garden visitation.

Janelle Hatherly 2021

Introduction

First and foremost, I am an educator specialising in creating meaningful learning experiences especially in the cultural sector. Based in Sydney Australia I have had the privilege of working at both the oldest museum (Australian Museum 1845) and oldest botanic garden (Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney 1816) in the country.

The heritage-listed Australian Museum is the fifth oldest natural history museum in the world and is located in Sydney’s central business district. The botanic garden and its surrounding urban parkland is the more spectacularly sited, occupying 64 hectares along the shores of Sydney Harbour. Located next to the iconic Opera House and Harbour Bridge (and with the Art Gallery of NSW within its grounds), it is one of the most visited gardens in the world with 3-7 million visitors annually.

The Royal Botanic Gardens and its surrounding Domain annually host masses of free and paid events, including our internationally broadcast New Year’s Eve fireworks. Together they are one of the top ten most-visited destinations in Australia for international visitors. They are much-loved and proudly owned by the local community.

The primary purpose of education is to foster a lifelong love of learning. As we enter The Information Age, educational tourism is becoming very popular and, as an educator, I believe our gardens (and museums) are uniquely placed to give visitors a powerful learning experience as well as a good time.

Current tourism statistics

As this is a gardens tourism conference I’d like to start by sharing the status quo of tourism in Australia and New Zealand. Australia is a very large continent with a relatively small population (less than 24 million people), and our domestic tourism is high. In the last year, nearly 80 million visits were made regionally, with many people making multiple trips and attending 2-3 events.

The latest statistics from Tourism Research Australia show that there has been an increase in all our key inbound markets. Of the 6.1 million international visitors last year to our reasonably remote shores, one third went to a botanical or other public garden. Many international visitors come to Australia primarily to see friends and relatives. If our locals love their botanic gardens then they are likely to take visitors there.

According to our professional organisation BGANZ (Botanic Gardens of Australia and New Zealand Inc.) there are about 140 botanic gardens in Australia and 22 botanic gardens in New Zealand for visitors to enjoy native and exotic plant collections ‘down-under’. New Zealand also has over 100 private and heritage gardens linked to New Zealand Garden Trust that are periodically open to the public.

My colleagues ‘over the ditch’ tell me that New Zealand tourism is doing very well. This is due in part to the significant increase of international tourists specifically travelling to see the locations of the movie sets for Tolkien’s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. Surveys show that 16 percent of their international visitors cited The Hobbit Trilogy as the initial reason they considered a trip to New Zealand. Surprisingly New Zealand gets half the number of international tourists Australia gets, yet its population is only a fifth of ours!

With such a small population, it is understandable that New Zealand has plenty of unspoilt natural beauty/wide open spaces for visitors to enjoy. Visiting public gardens is also amongst the most popular activities for visitors to New Zealand. Being located in close proximity to ‘Middle Earth’, Hamilton Gardens is now the largest tourist attraction in the Waikato Region with more than one million visitors annually. It is fascinating to see how the movie industry can change a small country’s economy and make a positive difference!

The Information Age

Before we see how public gardens are making a difference from an educational perspective, let’s first reflect on the world we currently live in. In the last two decades we have experienced huge global changes and faced challenges on all fronts … socially, environmentally and economically. The birth of the internet (a mere) 21 years ago started a Technology Revolution which is having as great an impact on humanity as the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions before it.

Technology has changed the way we communicate, do business and science. We now communicate through social media – with true democratization of knowledge and ideas. The dramatic increase in the number of connections we can now make has had volatile and unpredictable consequences and has contributed to the global financial crisis. Our computers can also manipulate ‘big data’ like never before. We have witnessed ground-breaking scientific research such as the mapping of the human genome and, through genomic sequencing, the ability to interpret the composition of whole ecosystems by studying a mere handful of soil humus. And most exciting, is how we can now explore the workings of the human brain.

Whereas in the past one could plan for the future with a pretty good idea of what the world would be like in 30 years’ time, now there is NO knowing. The Information Age is upon us and the future is not what it used to be! How then, does society prepare for an uncertain future, for careers and lifestyles not yet defined? How do we keep hope and optimism alive in the face of unprecedented and rapid change?

We can do this through the joys of learning. As long ago as 1954, Abraham Maslow postulated that humans are motivated to learn to satisfy needs, a condition that has evolved over tens of thousands of years. When humans take learning to its highest level we are rewarded with ‘a-ha’ moments of self-fulfilment and creative output. Physiologically, performing such cognitive tasks causes a higher release of dopamine in the human amygdala (in the mid-brain) and we feel happy. This feeling of happiness motivates us to try again until we learn more ... and more. Learning promotes learning and, with practice, every individual can experience a degree of self-actualisation and connection with something bigger than themselves.

I believe this will be the Unique Selling Proposition that sets botanic gardens, museums and galleries apart from all other tourist attractions. As well as being great recreational venues, our cultural institutions can be powerful learning environments and harbingers of hope. As Robert D Sullivan Former Assoc. Director of Public Programs Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum said:

“Our final products are not programs, but people: transformed, enlivened people who leave us different than they arrived; whose attitudes, beliefs, feelings, knowledge of the natural world and their place in it have been positively altered.“

And from St Thomas Aquinas, the C13th Italian Dominican monk and one of the greatest intellects of the Middle Ages: “You change people by delight. You change people by pleasure.“

Our Unique Selling Position (USP)

Positive attitudes foster learning. That’s why we must promote hope and optimism and avoid giving negative messages associated with environmental degradation, climate change and loss of biodiversity. Contrary to the current sentiments of ‘doom-and-gloomers’,

Road accidents have never been lower,

Car engines have never run cleaner or more efficiently (15 miles to gallon, now 35m/gallon),

Farm productivity has increased more than 200% since the 1950s,

More people are literate now than ever in history (86% with youth literacy at 91%), and

Stranger danger has no grounds in statistics – nothing has gone up – it’s an illusion.

With access to a smart device every individual can experience a degree of self-actualisation and even if it doesn’t get them out of their poverty cycle it can provide a much better escape experience than drugs. ‘A smart device can set you free!’

The internet may be changing our lives forever but, really, the glass is half-full … and, anyway, optimists have more fun and live longer! For those of us privileged to work in public garden tourism, our role is to help humanity celebrate the remarkable and awesome world of nature.

Where we are affects how we think and behave. If education is a high priority our gardens are optimal environments for life-long learning and attitudinal change. In the peace and tranquillity of a botanic garden all our senses are stimulated and we find time to think. We attempt to make sense of our surroundings and make meaningful connections. We all learn differently and gardens can cater for all preferred learning styles/interests.

Brain imaging studies show that information from each of the senses is stored in different parts of the brain but they are all interlinked by dendritic extensions of neurons. When similar interest is triggered, often later in another environment, multiple neurological pathways fire at once and memory making is strengthened. This is the power of school excursions – most adults can remember going on one.

Children are naturally curious. With our support and encouragement, they can start their own journey of lifelong learning.

These little children are taking part in a ‘What we get from plants?’ lesson. As you can see, they are totally absorbed trying to work out if a cork, rubber bands, paper, cotton clothing, marbles etc. are made from plants. With instruction by a trained educator, the lesson goes on to ask: “What happens if we must harvest plants, chop down trees for our needs?” It is then easy to get across the message that if we are to sustain our environment we need to reduce, reuse and recycle. Many students experience an extra ‘a-ha’ moment in botanic gardens when they realise that all of the products humans use ultimately come from plants or rocks. Thus begins their lifelong connection with conservation of Earth’s natural resources.

We can’t hang on to youth forever but we can stay learners all our lives. Plants and botanic gardens are the best teachers. Those of us involved in botanic education often marvel at how easy it is to get kids of all ages excited about plants and gardening. Gardening is hands-on and truly interactive and can be done by people of all ages, backgrounds, social status, interest levels and abilities. The rewards and sense of achievement are instant – (the satisfaction of successfully planting something) and ongoing (watching it grow and produce flowers or fruit).

I recall a great revelation when our education horticulturists first went beyond the garden walls and worked with socially disadvantaged groups in the community – both adults and youth. I saw how learning ‘by doing’ came naturally with horticulture. By doing, the community could ask for guidance when they needed it. We could then tailor training sessions – varying the length and level accordingly. We always sought feedback, going so far as to hand out evaluation sheets, so that we could improve our own skills. This built positive esteem in all.

A non-learning situation would have been to give the community the training we thought they needed. This is a recipe for failure. It is said that the key to education for sustainability (EfS) is to be ‘futures focused’. What could be more optimistic than undertaking a garden project? Imagining the future and planning for change – whether it is next week, next season or next year, is helping our local communities adapt to a rapidly changing world.

It is relatively easy for garden educators to create learning opportunities for known audiences (such as school groups and the local community – on-site and off-site) but engaging the minds of casual tourists to our gardens requires greater organisational input and understanding of the visitor experience. Everything created must be underpinned by sound communication and evaluation strategies. Every branch of the organisation should feel part of a holistic learning community contributing to the well-being of the gardens and everyone within it.

To work out how to get visitors to connect with and interpret our collections, everyone involved needs to think like a visitor/be a visitor. Staff, volunteers and visitors need to be actively/not passively engaged. Visitors are not students, but are co-learners, just like us.

As an organisation and within working teams, we need to address the following:

Some examples of effective interpretation

There are different ways to produce signage … from the traditional 2D image on a stake in the ground to innovative ways that take advantage of contemporary technologies. Virtual and real alternatives can co-exist.

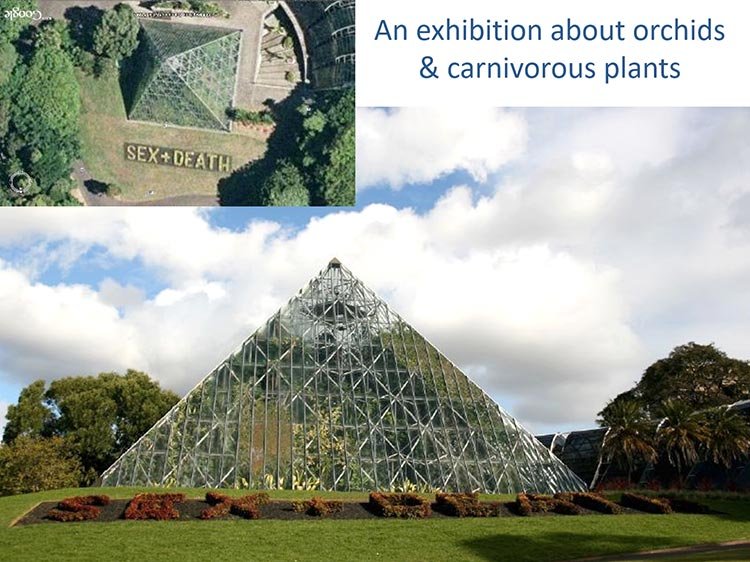

Curated plant collections can be interpreted in engaging and colourful thematic displays and promoted using social media. Utilising the extensive collection of orchids and carnivorous plants in its greenhouses, the Royal Botanic Gardens created a Sex and Death exhibition to connect people with plants. Its outdoor signage was the most photographed image on social media for some time … and it even made it on Google Earth!

Environmental, cultural and scientific concepts like managing wildlife, interpreting Aboriginal heritage and understanding evolutionary processes can be explained intelligently and enjoyably. Remember, when we are relaxed, we are more receptive and open to new ideas. When socialising we can discuss issues and help each other learn.

There’s absolutely no need to ‘dumb down’ anything as you showcase what your organisation is proud of and stands for. If you also provide intelligent public programs … the possibilities are endless. The best learning interactions occur when staff and docents connect with visitors through plants.

In summary:

Other perspectives on garden tourism

To finish I’d like to share with you some contemporary wisdom from some of my Australian colleagues who are not educators. Your organisation rightly recognised Catherine Stewart’s excellent Garden Drum website with an International Garden Tourism Award this year.

When I met up with her recently, she added this insight:

“Your product is the garden and in this new world, information must be free, easily accessed and of a high quality. Websites without photos, with limited information and an expectation that ‘you can pay me to find out’ are naïve and old culture. Today there are many platforms for communication and one size no longer fits all. And how much easier (and cheaper) it is to update information on-line than update and distribute a printed brochure!”

Catherine believes this is where marketing and communication staff should be channelling their efforts.

Academic and ecotourism expert Jan Packer has recently conducted research into the restorative benefits of being in a museum or a botanic garden.

Jan found that while museums enable people to switch off and temporarily escape the stresses of everyday life, public gardens have positive health benefits with participants reporting increased sense of well-being.

I interviewed Dr Judy West for the March 2015 issue of the BOTANIC GARDENer and she commented on the many ways visitors use the ‘place’. For example, the Chair of one of Australia’s major medical organisations was telling her that he brings people to the gardens who have recently been diagnosed with serious medical conditions to discuss this and what it might mean for their future. They find a quiet place to sit somewhere in the gardens rather than visit the coffee shop. The value of this to society can’t be underestimated.

Judy is also a scientist and highlighted the role of ex-situ collections in informing general public about contemporary environmental challenges and the work involved in in-situ conservation. Above is the new Daisy display at the Australian National Botanic Garden in Canberra. (It is also featured in this issue of the magazine).

Dale Arviddson, our current BGANZ President, gave weight to the relevance of regional botanic gardens. He explained how botanic gardens are often funded by regional councils and the only way they become serious proposals is when they support a recreation function for locals and are a tourist attraction. The sites chosen may not necessarily be the most suitable for growing plants.

This is the Mackay Botanic Garden. $15 million was given to set it up on a 51-hectare site. Half the funds were for conservation and showcasing local flora (a key role of a botanic garden) and the other 50% to create a tourist attraction. Dale explained how this large-scale dramatic landscape was built on the fringe of the city to cater for the mass tourism market. We discussed how attractions must be easily accessible and highly visible and how many visitors just want an instant ‘wow’ factor which only takes them 25-30 mins to experience.

The award-winning Australian Garden at Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria - Cranbourne Gardens has huge bowl vistas which are an instant attraction for Asian bus tourists. In the very short time span available to this type of tourist, they can take happy snaps and get an overview of what’s there … and can say they ‘saw it and did it all!’

The central viewing platform (just beneath the slide heading) is also easily accessed by the growing markets of elderly, grey nomads and visitors with limited mobility. In both the above examples, the landscape designers were mindful of locating the car park nearby and providing easy orientation such as wayfinding signs to designated areas on coloured poles.

You might think this fleeting experience goes against the learning principles I espouse as a key role for botanic gardens. Fortunately, if we ensure this type of visitor’s impression is truly memorable (and they can take good photographs) they will recount their experience to others long after the event. Hopefully they will be motivated to learn more on-line or they might even commit to make a longer visit next time.

Public gardens should be places of self-discovery. Let’s now consider the free independent travellers (FITs) who enjoy independent discovery. These visitors want a longer visit (at least two hours) and rather than wander aimlessly they need to be attracted/escorted around the site – ideally by the landscape itself. Visitor-focused planning ensures pathways lead around and into the gardens where visitors will encounter a series of rooms – complete with signage, interpretive and theatrical elements.

Another growth market is nature-based tourism. As the human population and the built environment increases, the natural environment is becoming scarcer. Many tourists want to explore nature but are unfamiliar with it so prefer nature when it is tamed – neat paths, manicured green grass, shady trees – and full of that familiar life form, humans.

By incorporating wilderness within our garden walls, we can provide a safe adventure and foster greater appreciation of native flora. These areas also attract birdwatchers and anyone interested in seeing wildlife in nature. Botanic gardens around the world have added whole natural ecosystems to their estates and are expanding their conservation role to include seed banking.

For example, in Sydney we protect nationally endangered Cumberland Plain Woodland within our Mount Annan Botanic Garden estate. As a consequence of threats such as clearing and weed invasion, this ecological community is now restricted to relatively small and fragmented bushland patches nestled among largely urban to peri-urban environments.

Conclusion

Thank you for the opportunity to showcase the work being done in public engagement ‘down under’. We are all engaged in this great enterprise and are trying to give our visitors and tourists a special experience. For some people this might be the best trip of their lives, and with the imaginative use of modern technology, we can offer them beauty, escapism and novelty. Gardens have a special magic that can help people really see plants like never before and understand their importance so much more.

© Janelle Hatherly

Please credit www.janelle.hatherly.com if you use any information in this article.

If you have any questions please get in touch.